If you’ve been in a staff meeting, scrolling social media, or reviewing curriculum materials lately, chances are you’ve heard the phrase Science of Reading more times than you can count. For some educators, it brings clarity and validation. For others, it can feel overwhelming, confusing, or even polarizing – especially when it’s framed as something new or separate from what teachers are already doing. So let’s slow it down and ground ourselves in what the research actually says.

If you’ve been in a staff meeting, scrolling social media, or reviewing curriculum materials lately, chances are you’ve heard the phrase Science of Reading more times than you can count. For some educators, it brings clarity and validation. For others, it can feel overwhelming, confusing, or even polarizing – especially when it’s framed as something new or separate from what teachers are already doing. So let’s slow it down and ground ourselves in what the research actually says.

The Science of Reading isn’t a program, a checklist, or a one-size-fits-all solution. It’s a body of research – decades in the making – that helps us understand how children learn to read and what instructional practices best support that process.

In this first part of our three-part series, we’ll focus on:

- What the Science of Reading actually is

- Common misconceptions

- The key components every teacher should understand

Let’s unpack the science behind how kids learn to read- not to put more on teachers’ plates, but to clarify and support day-to-day instruction.

What Is the Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading refers to a vast body of interdisciplinary research from cognitive science, linguistics, neuroscience, and education. Together, this research explains how the brain learns to read and what instruction helps most students become skilled, confident readers.

One of the most important findings? Reading is not an innate, natural process. Unlike spoken language, which children typically acquire through exposure and interaction, reading requires the brain to link sounds, symbols, and meaning in ways that require new pathways to be forged. This means that most children need explicit, systematic instruction to become proficient readers.

When educators and policy makers refer to the “Science of Reading,” they are referring to the research that helps us answer questions like:

- Why some students struggle to decode words even when they understand language well

- Why fluency matters for comprehension

- Why some “good guessers” appear to read well early on but struggle later

Understanding the science behind why reading is hard can help us teach it more effectively and more compassionately.

What the Science of Reading Is Not

Because the term has gained so much attention, it’s often misunderstood. Let’s clear up a few common myths:

- It is not a curriculum! There is no single “Science of Reading program.” Instead, the research helps us evaluate whether instructional materials and practices align with what we know about how reading develops.

- It is not just phonics! Phonics is essential—but it’s only one piece of the reading puzzle. A phonics-only approach without attention to language, meaning, and knowledge is incomplete.

- It does not replace rich literature or meaning-making. The goal of foundational skills instruction is to unlock comprehension, not replace authentic reading experiences. The research around the science of reading is essential to developing true comprehension in students.

The Science of Reading is about making informed, research-backed decisions about what to teach, when to teach it, and how to best support students.

The Big Picture: How Reading Works

A helpful way to understand the Science of Reading is through the Simple View of Reading, which explains that:

Reading Comprehension = Word Recognition × Language Comprehension

Both parts are necessary, and both must grow over time.

- Word Recognition includes phonological awareness, phonics, decoding, and fluency. This is how students accurately and efficiently read the words on the page.

- Language Comprehension includes vocabulary, background knowledge, syntax, and the ability to make sense of spoken and written language.

A student may decode fluently but struggle to understand a text due to limited vocabulary or background knowledge. Likewise, a student with strong oral language may still struggle to comprehend if decoding is slow or inaccurate. Effective reading instruction strengthens both sides of the equation.

Meaning, Knowledge, and Language

The Science of Reading does not stop at decoding. In fact, research emphasizes that comprehension grows through language and knowledge-building over time. Students understand texts better when they:

- Learn and use rich, precise vocabulary

- Build background knowledge through science, social studies, and content-rich read-alouds

- Engage in meaningful oral discussions about texts

- Hear complex language modeled regularly

This is why read-alouds, interactive discussions, and content-area literacy are so powerful. They expand students’ understanding of the world and build context for students to draw on when they read independently.

Equitable Instruction for ALL Learners

When reading instruction relies on implicit strategies—like guessing from pictures or “figuring it out”—students who don’t already have strong literacy exposure are left behind.

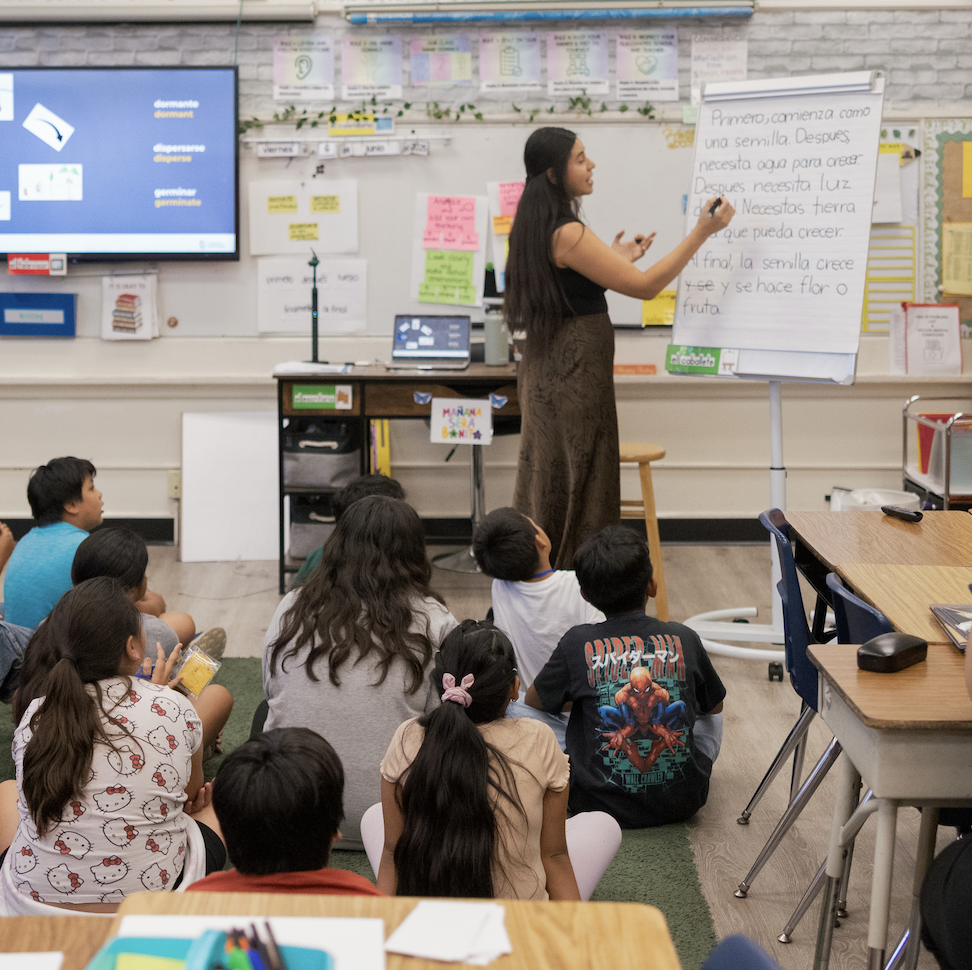

The Science of Reading reminds us that clear, explicit instruction is an equity issue. When we teach foundational skills, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies directly, we remove barriers and increase access for all learners.

Effective instruction doesn’t lower expectations- it provides the tools students need to meet them.

Looking Ahead

Understanding the Science of Reading helps us make smarter instructional choices- not by discarding everything we already do, but by grounding our decisions in research and evidence.

In Part 2, we’ll explore what this looks like in practice in the classroom: how to balance skills and meaning, how reading and writing support one another, and how this research applies beyond the primary grades. In Part 3, we’ll take a look at how families and caregivers can implement the science of reading at home, building on school practices to encourage confident reading across settings.

Here are some additional resources that can provide support as you dive deeper into the Science of Reading:

Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom

A Fresh Look at Phonics, Grades K-2: Common Causes of Failure and 7 Ingredients for Success